Recent LLMs can use filler tokens or problem repeats to improve (no-CoT) math performance

AI can sometimes distribute cognition over many extra tokens

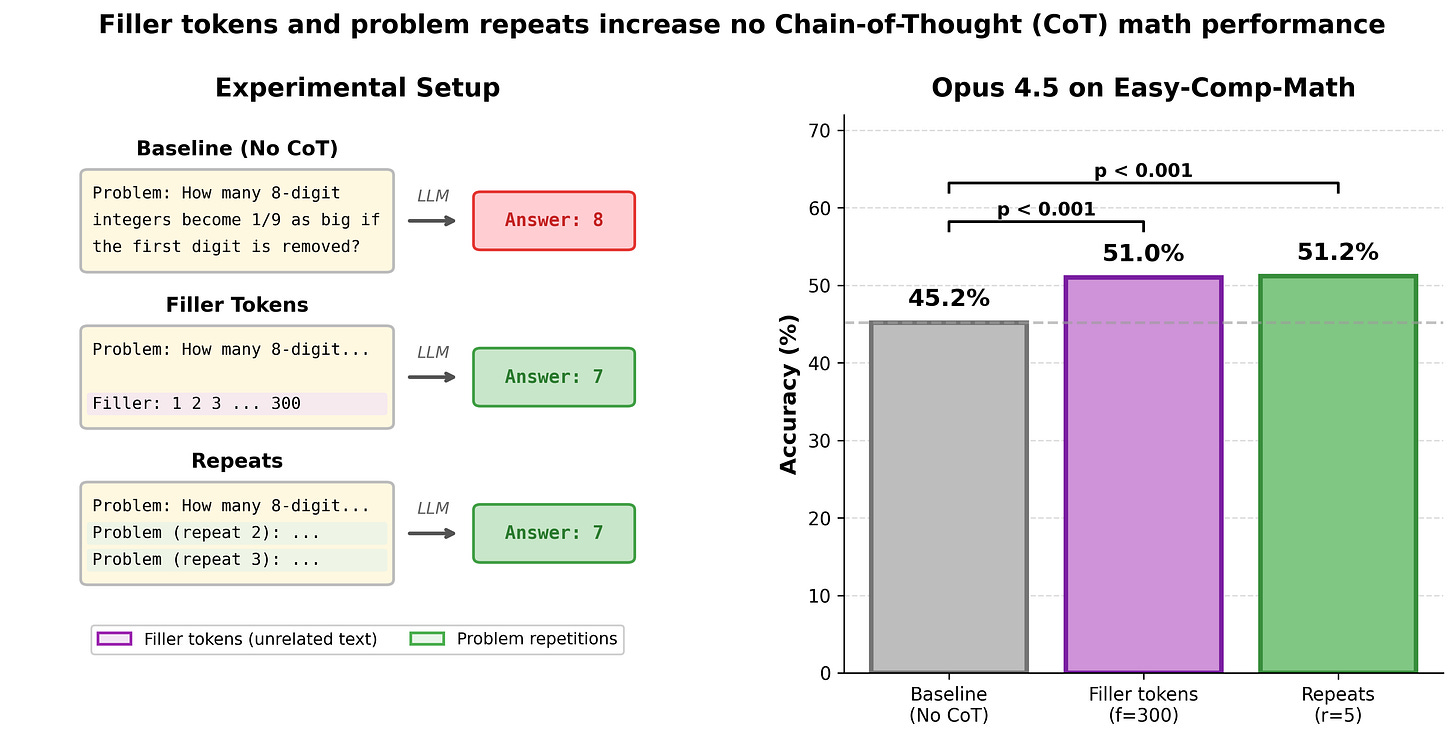

Prior results have shown that LLMs released before 2024 can’t leverage ‘filler tokens’—unrelated tokens prior to the model’s final answer—to perform additional computation and improve performance.1 I did an investigation on more recent models (e.g. Opus 4.5) and found that many recent LLMs improve substantially on math problems when given filler tokens. That is, I force the LLM to answer some math question immediately without being able to reason using Chain-of-Thought (CoT), but do give the LLM filler tokens (e.g., text like “Filler: 1 2 3 ...”) before it has to answer. Giving Opus 4.5 filler tokens2 boosts no-CoT performance from 45% to 51% (p=4e-7) on a dataset of relatively easy (competition) math problems3. I find a similar effect from repeating the problem statement many times, e.g. Opus 4.5’s no-CoT performance is boosted from 45% to 51%.

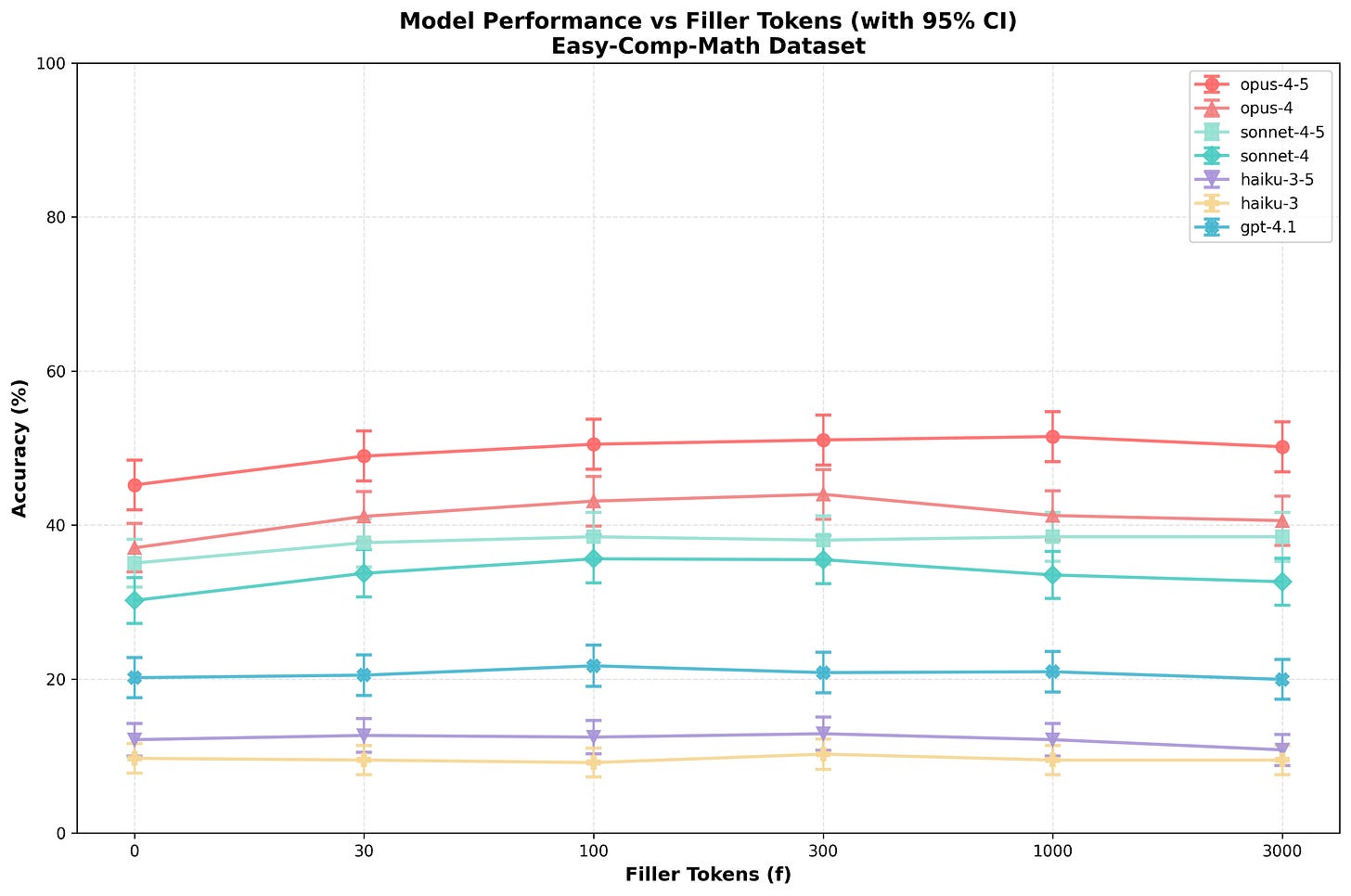

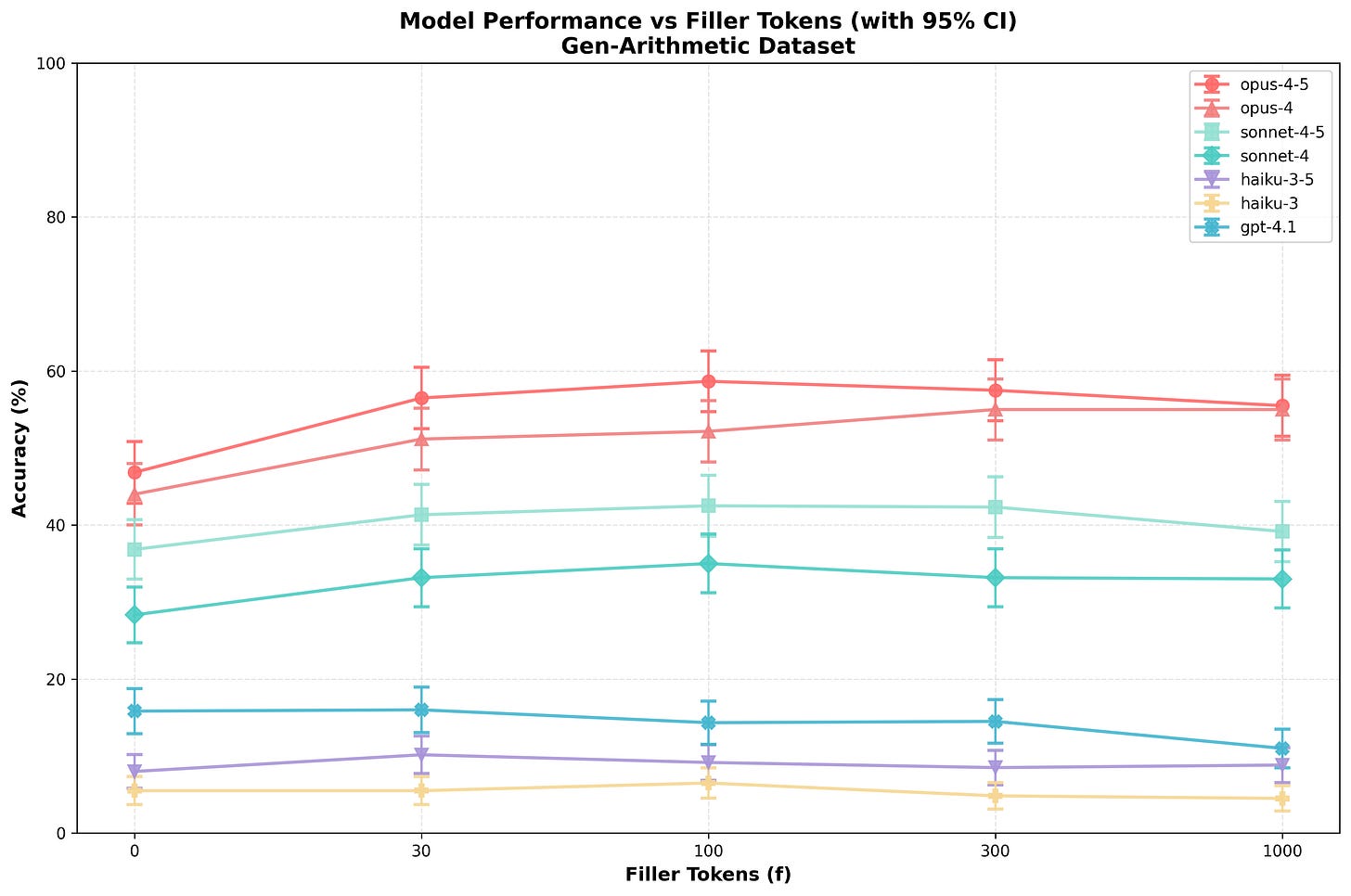

Repeating the problem statement generally works better and is more reliable than filler tokens, especially for relatively weaker models I test (e.g. Qwen3 235B A22B), though the performance boost is often very similar, especially for Anthropic models. The first model that is measurably uplifted by repeats/filler is Opus 3, so this effect has been around for a while. Performance smoothly increases with the number of repeats/filler tokens, though using a very large number of filler tokens often degrades performance.

The math datasets I use aren’t particularly chosen such that it is easy to parallelize cognition, and I think math problems are especially serial relative to other types of cognitive work.4 That said, the datasets I use are relatively arithmetic heavy, and repeats/filler tokens seem particularly helpful for arithmetic. These results neither demonstrate nor rule out that repeats and filler tokens are only helpful for arithmetic: the results I see are totally consistent with this and I haven’t done analysis that lets us more precisely answer this question.5 I do find that repeats/filler tokens are still helpful on word problems and problems that have large non-arithmetic components (e.g. for humans, little of the difficulty would be the arithmetic), but this could still be explained by repeats/filler tokens only being helpful for arithmetic and models being limited by arithmetic even on problems with large non-arithmetic components (even though most of the difficulty for humans is something else).

Overall, these results demonstrate a case where LLMs can do (very basic) meta-cognition without CoT. This is not a recent development (it occurs for Opus 3) and other results demonstrate recent LLMs have minimal control of internal states, implying that recent frontier LLMs could have somewhat sophisticated meta-cognitive abilities. Further research is needed to better characterize these abilities. Ideally we wouldn’t only discover meta-cognitive abilities are present long after they emerge (as is the case with this result)!

Code for these experiments can be found at github.com/rgreenblatt/no_cot_math_public.

[Thanks to Fabien Roger for an initial discussion about no-CoT math performance that inspired these results. Thanks to Fabien Roger for running some evaluations for me on Opus 3, Sonnet 3.5, Sonnet 3.6, and Sonnet 3.7 (these models are no longer publicly deployed by Anthropic). Thanks to James Lucassen, Alex Mallen, Buck Shlegeris, Fabien Roger, and Tao Lin for comments and/or discussion.]

Datasets

I run experiments on two datasets of math problems that I created:

Gen-Arithmetic: This consists of 3000 generated arithmetic problems using Python syntax like “(77 - -56) - (-65 - (((-35 * 23) // 30) * -68))”. Expressions are built from integers from -99 to 99 and have 5 to 7 operations (6 to 8 integers). For some experiments I only use 600 problems. See generate_arithmetic_problems.py in the open source repo for more details.

Easy-Comp-Math: This consists of 907 mostly easy competition math problems. Here is an example problem: “If (x2+3x+6)(x2+ax+b)=x4+mx2+n for integers a, b, m and n, what is the product of m and n?” (Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets this problem right and it gets problems rated as being this hard right 38% of the time.) This dataset consists of around 600 (easy) middle school competition math problems from MATHCOUNTS and around 300 problems from relatively obscure Hungarian high school math competitions. Many of the MATHCOUNTS problems just require some pretty basic algebra and then some arithmetic. I’m pretty confident this dataset isn’t strongly contaminated but it is plausible that contamination materially affects the results and the problems might be highly similar to problems that the AIs have memorized. I’ll discuss this dataset more in “Appendix: more information about Easy-Comp-Math”.

Prompt

I use few-shot prompting (with 10 shots) with each “shot” appearing as another pair of user/assistant messages. The problems for the few-shot come from the corresponding dataset (either Gen-Arithmetic or Easy-Comp-Math).

For repeating N times the user message is:

You will be given a math problem. Answer immediately using the format 'Answer: [ANSWER]' where [ANSWER] is just the numerical answer, nothing else. No explanation, no words, no reasoning, just the number.

Problem: {Problem}

Problem (repeat 2): {Problem}

Problem (repeat 3): {Problem}

...

Problem (repeat {N}): {Problem}

For filler tokens through N the user message format is:

You will be given a math problem. Answer immediately using the format 'Answer: [ANSWER]' where [ANSWER] is just the numerical answer, nothing else. No explanation, no words, no reasoning, just the number. After the problem, there will be filler tokens (counting from 1 to {N}) to give you extra space to process the problem before answering.

Problem: {Problem}

Filler: 1 2 ... {N}

Note that a filler number of “N” doesn’t necessarily correspond to N filler tokens: sequences like “1 2 3 4” might have additional tokens for spaces (depending on the tokenizer), there are a few additional tokens added (”\n\nFiller:”), and there are a small number of other filler-like tokens added by default.

Anthropic models support prefilling the assistant message and I prefill with “Answer:”. For other models (which don’t support prefilling), I append “Answer:” to the user message.

Results

Performance vs number of repeats/filler

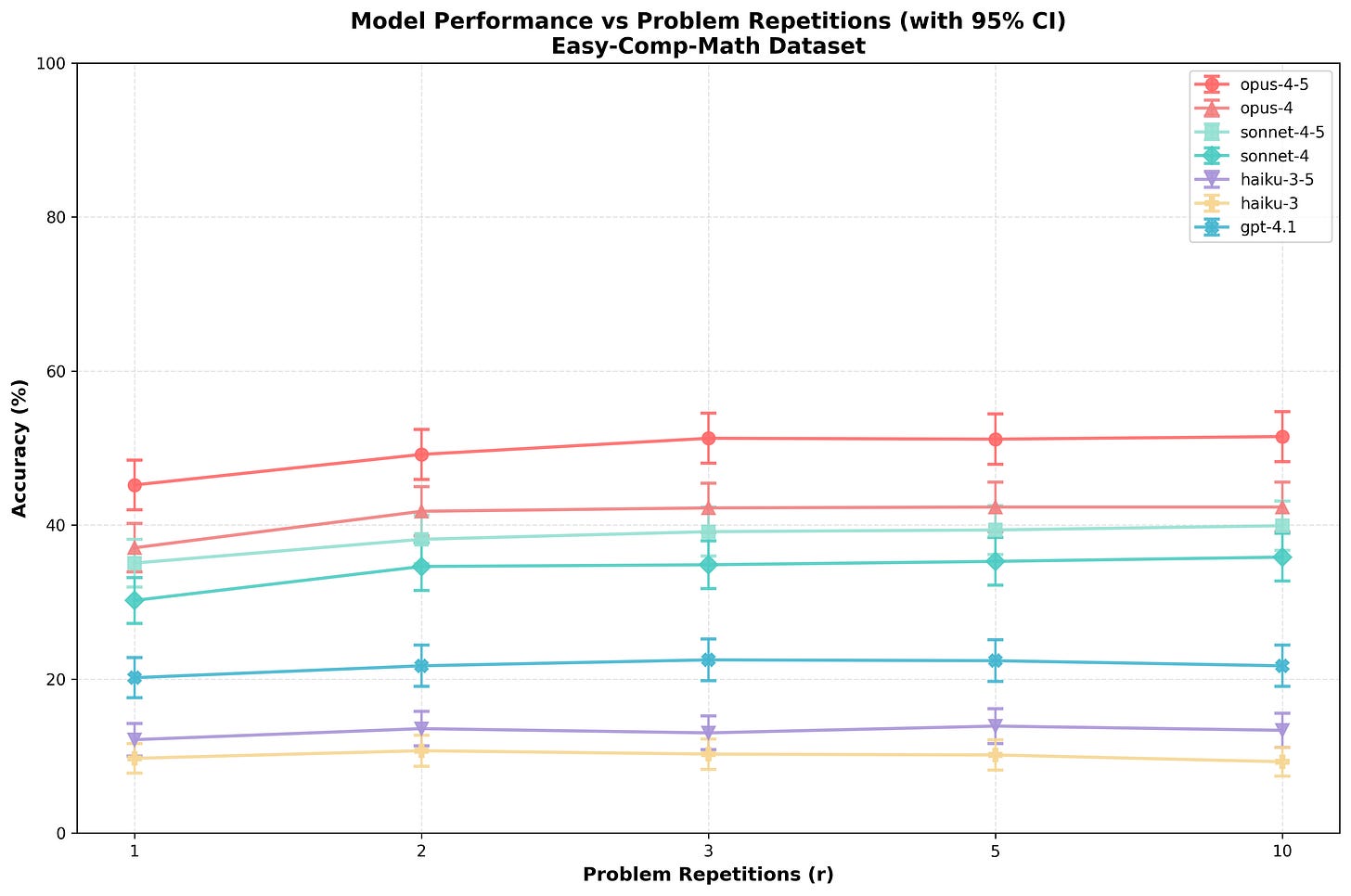

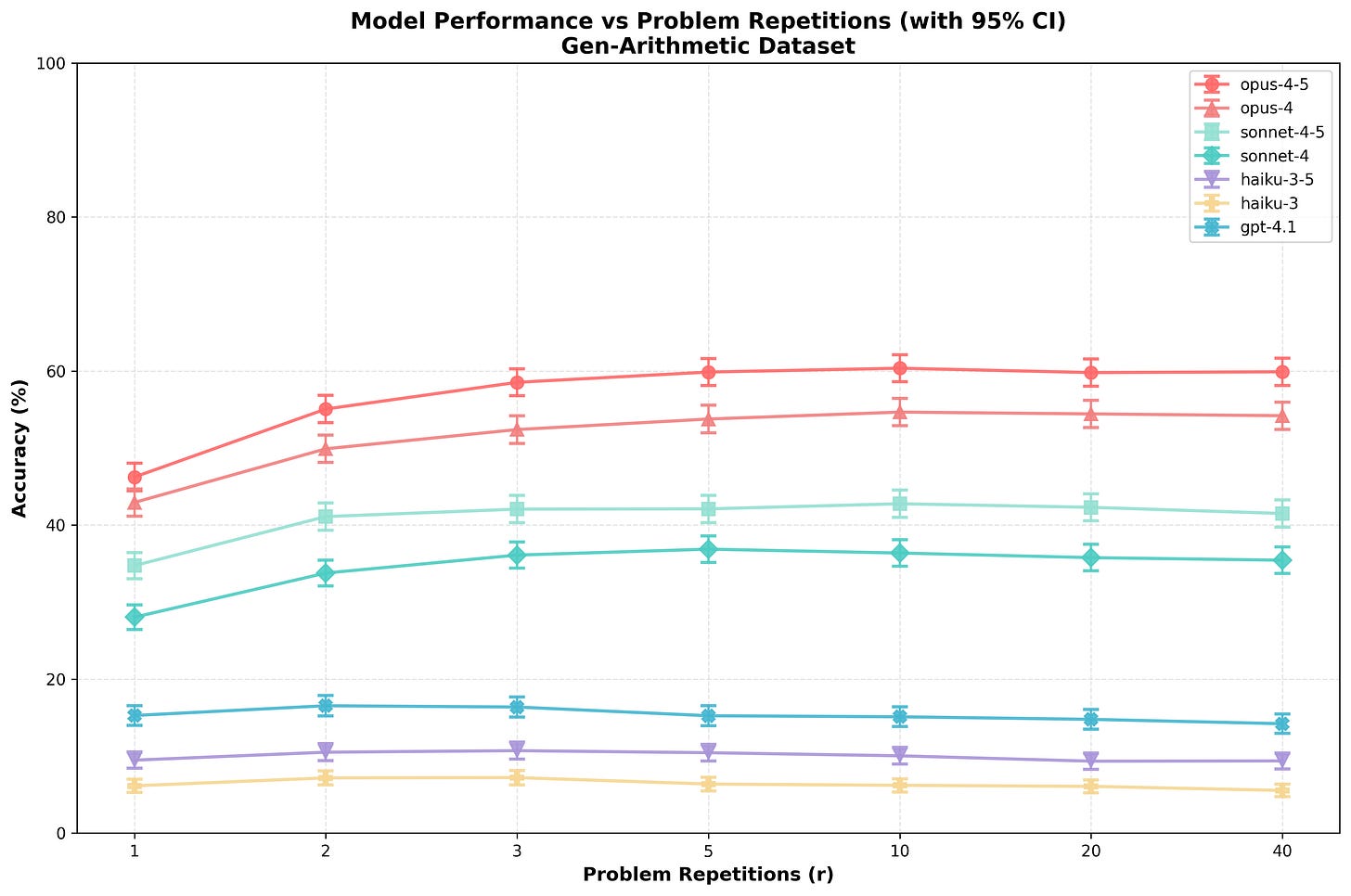

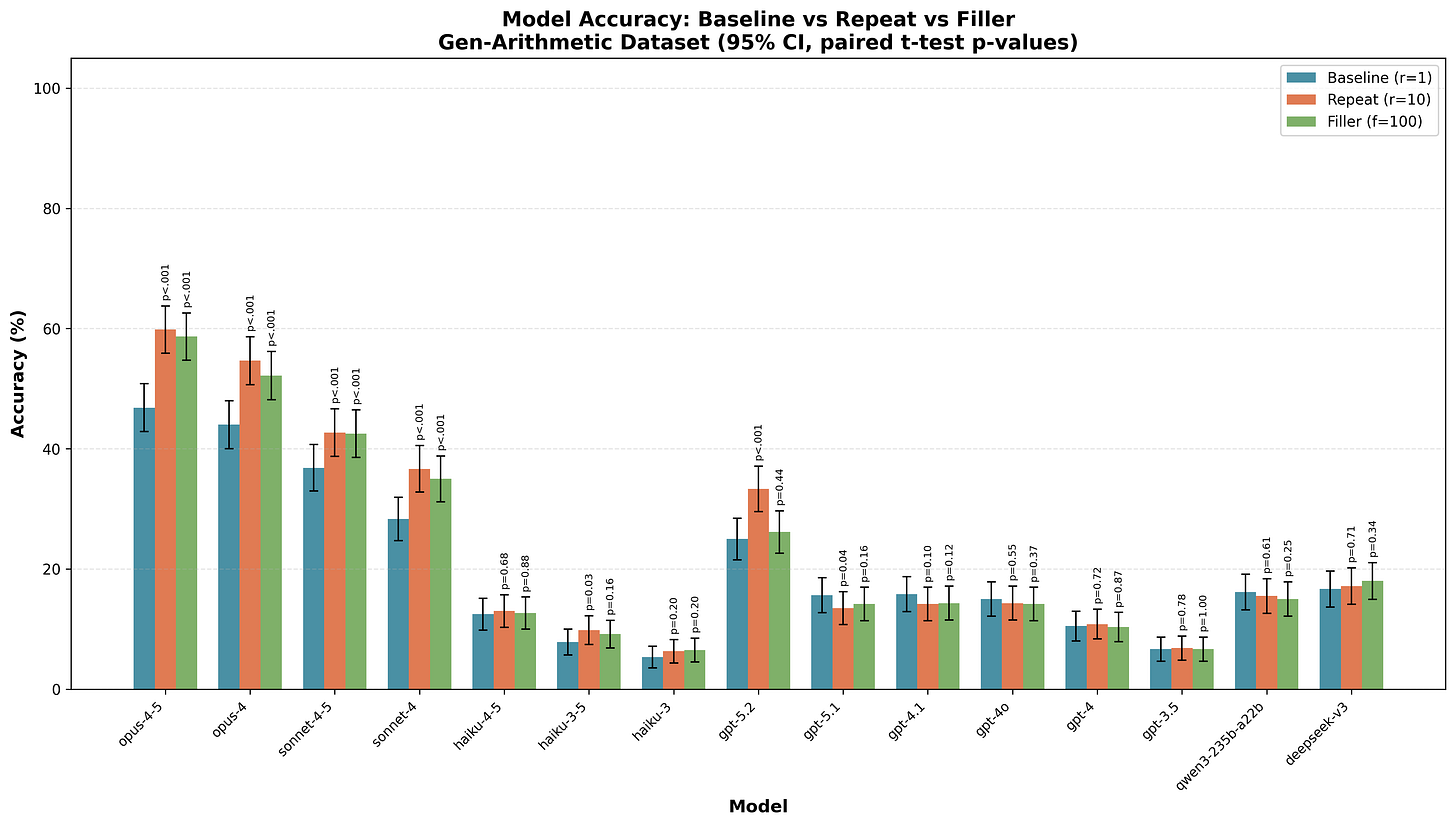

I observe relatively smooth performance increases for both repeats and filler tokens in both datasets, with (generally) stronger increases in performance due to repeats/filler tokens on Gen-Arithmetic:

When comparing with a paired t-test, many of these differences are extremely significant. See “Appendix: significance matrices” for details.

More generally, whenever I report a p-value, I’ll use paired t-tests to assess this. This results in much stronger statistical power because the problems that a given model gets right with/without repeats/filler are highly correlated.

Alternative types of filler tokens

I test out using “ …” and lorem ipsum as filler instead of counting (“1 2 3“ and so on). For Opus 4.5 and the Easy-Comp-Math dataset, baseline (no filler/repeats) performance is 45%, using counting to 300 as filler gets 51%, repeating “ …” as filler gets 50%, and 300 words of lorem ipsum gets 51%. It seems that many types of filler tokens can be used.

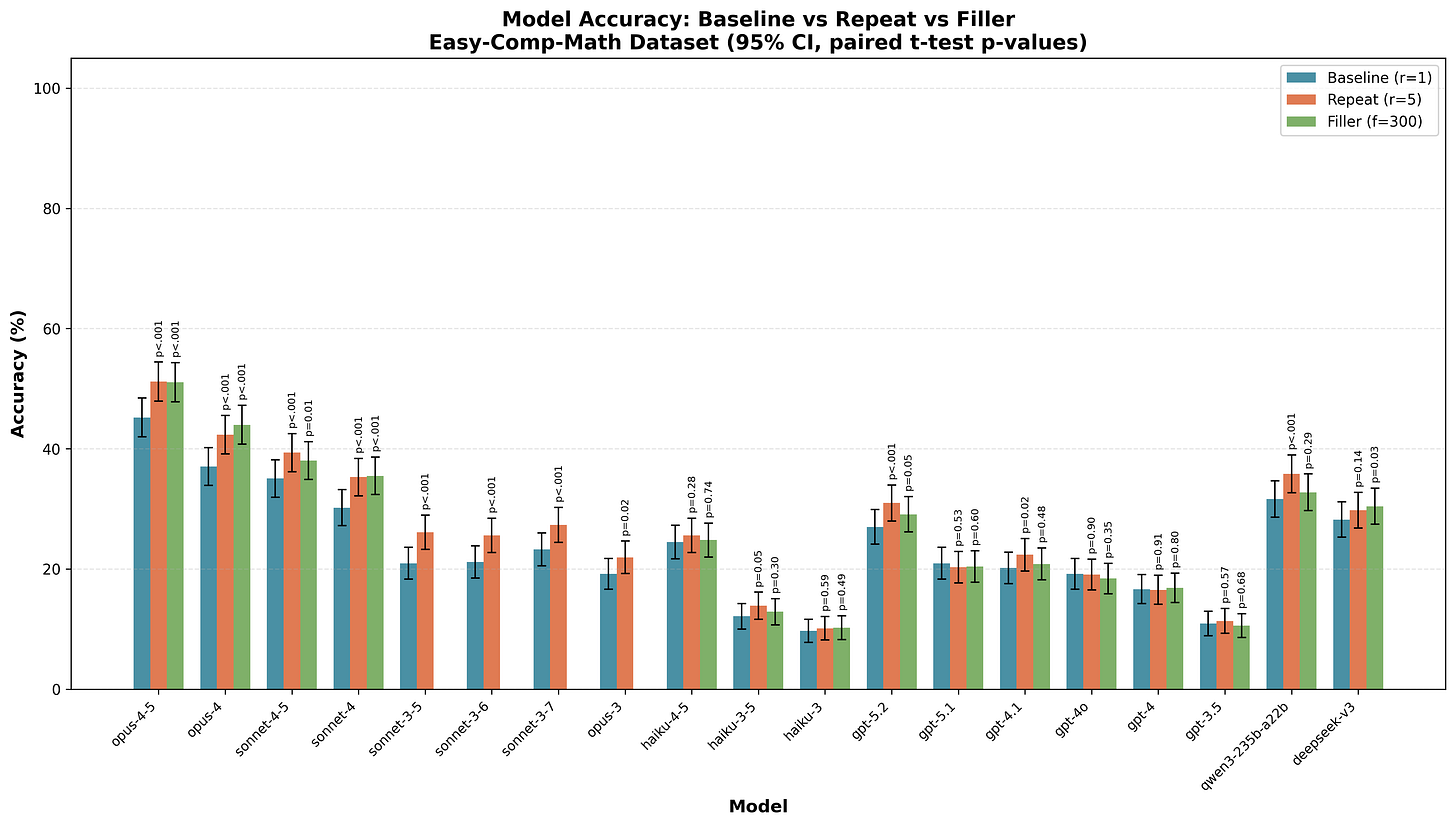

Minimal comparison on many models

I only ran these full sweeps over the number of repeats and the filler number for some Anthropic models (Opus 4.5, Opus 4, Sonnet 4.5, Sonnet 4, Haiku 3.5, Haiku 3), but I ran a more minimal comparison for a larger range of models comparing no filler/repeats to what appeared to be the optimal quantity of filler/repeats based on the larger sweep on Anthropic models.6 (r=5 for Easy-Comp-Math, r=10 for Gen-Arithmetic, f=300 for Easy-Comp-Math, f=100 for Gen-Arithmetic.7)

Here is a full bar chart with these results:

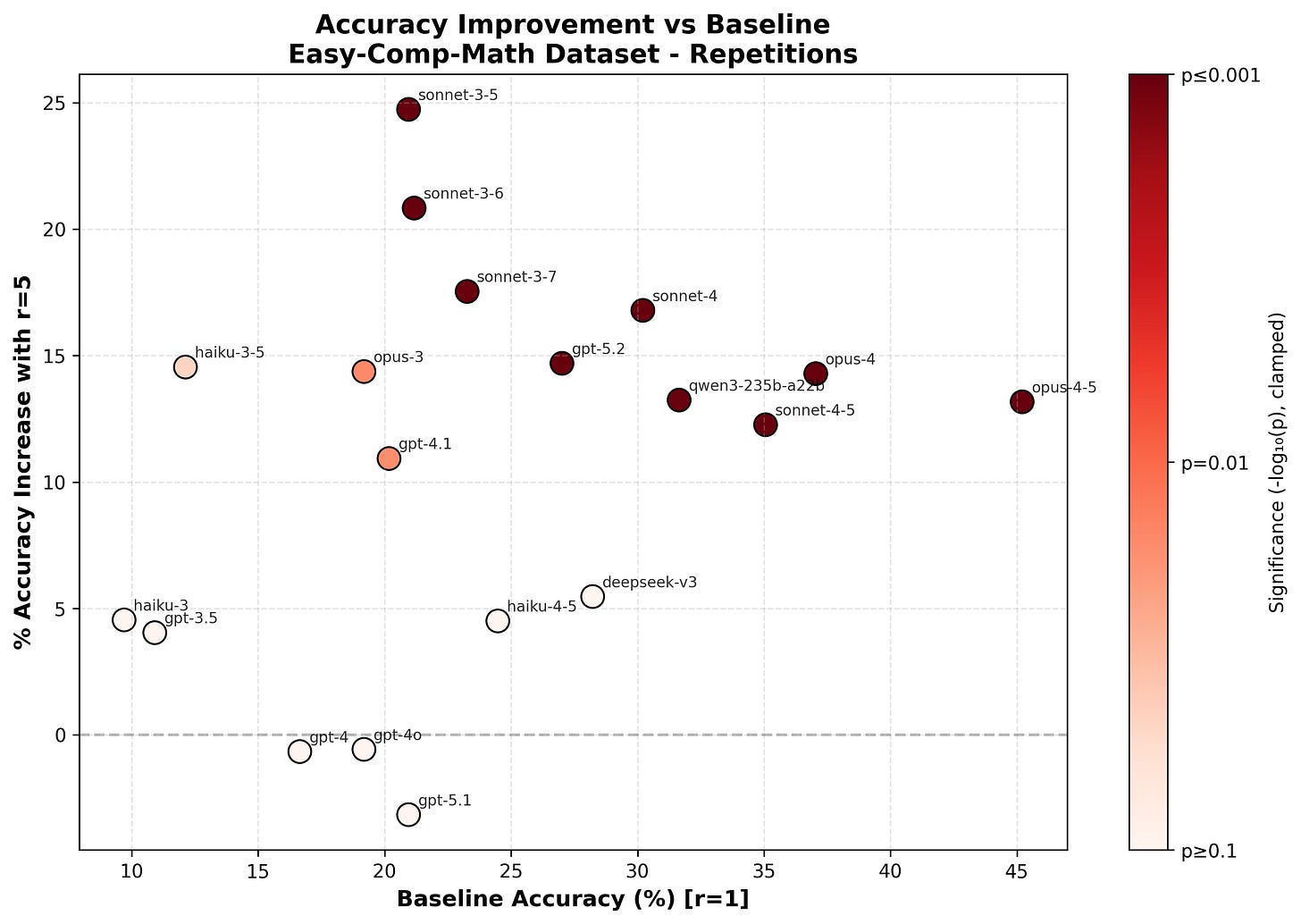

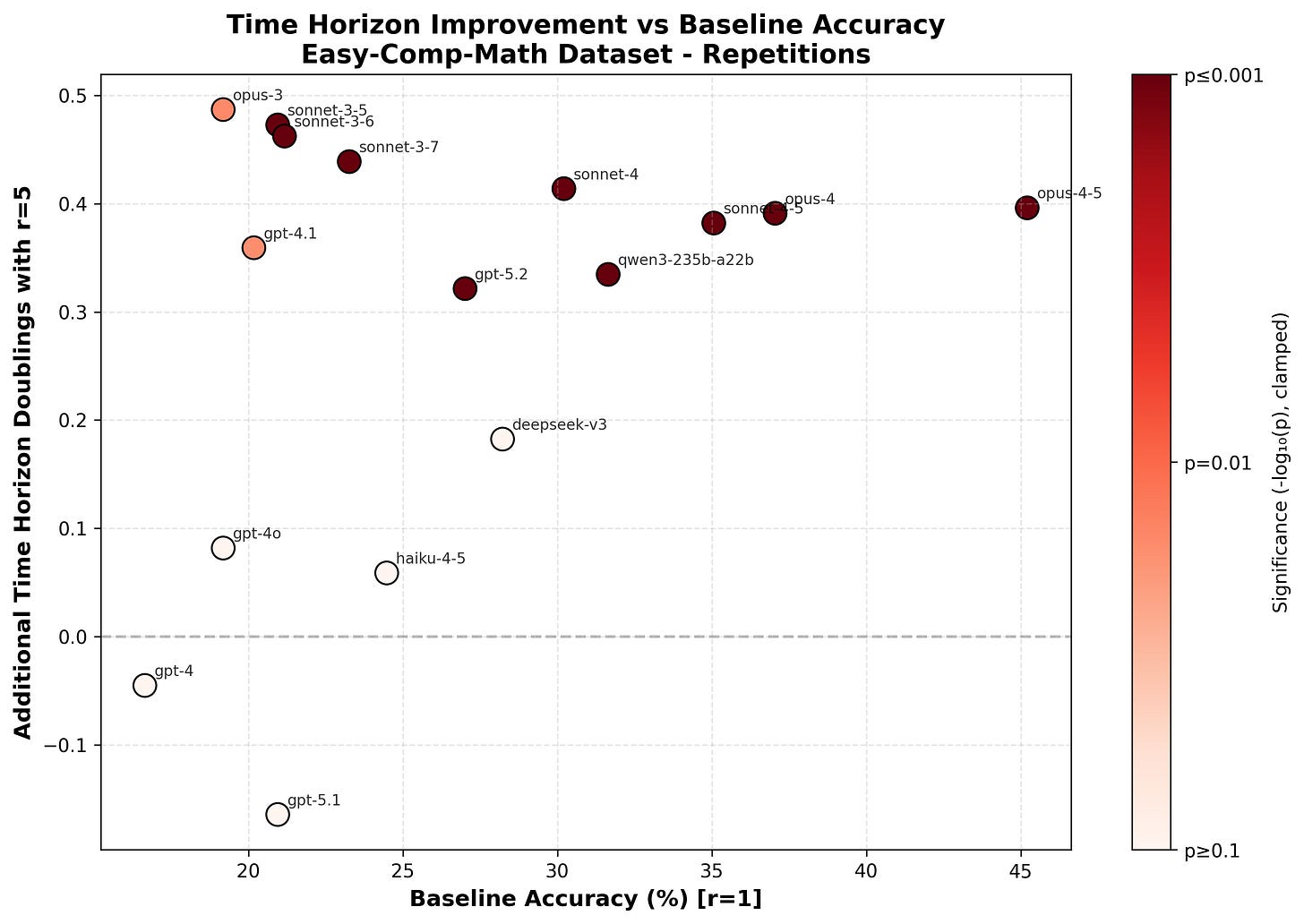

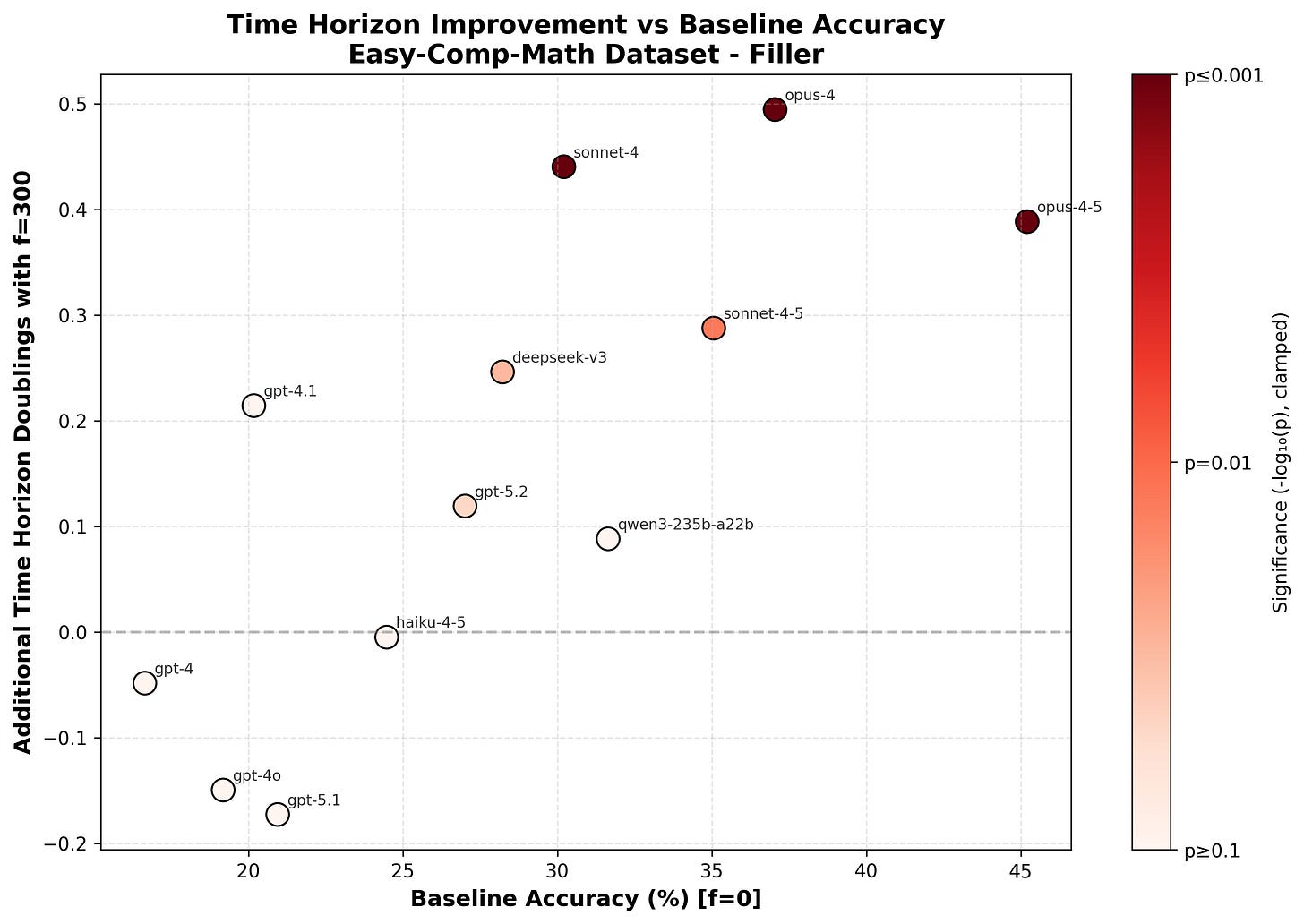

Relative performance improvement vs default absolute performance

We can look at which models are helped by repeats/filler and how this relates to the “default” level of performance (e.g., at what level of no-CoT math performance do repeats start helping). To quickly read this off, I find that it’s helpful to plot the relative performance improvement caused by repeats/filler versus the absolute performance without repeats/filler. The relative performance increase is computed as “performance with repeats or filler / default performance - 1”.8

I’ll just show this for repeats and Easy-Comp-Math here to save space, but other charts can be seen in “Appendix: more plots”

It’s not clear that comparing relative performance increase between different models is that meaningful: the models can solve different subsets of the problems and the distribution of difficulty is somewhat arbitrary so a 10% improvement for Opus 4.5 could mean something very different than a 10% improvement for Opus 3. Thus, this doesn’t clearly tell us if the relative uplift from filler/repeats is increasing/decreasing and it’s very non-obvious whether the correct interpretation is that Sonnet 3.5 is uplifted much more than Opus 4.5 (the relative uplift is much larger for Sonnet 3.5 but the absolute uplift is a bit larger for Opus 4.5). One way to resolve this problem is to change our y-axis to some unit where we’d expect that an improvement by 1 corresponds to roughly the same amount of progress regardless of the baseline value. A proposed unit that might have this property is log time horizon as introduced in Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks. An increment by 1 on log (base 2) time horizon corresponds to a doubling of time horizon and we might hope that a doubling of time horizon means roughly the same thing regardless of the initial time horizon.

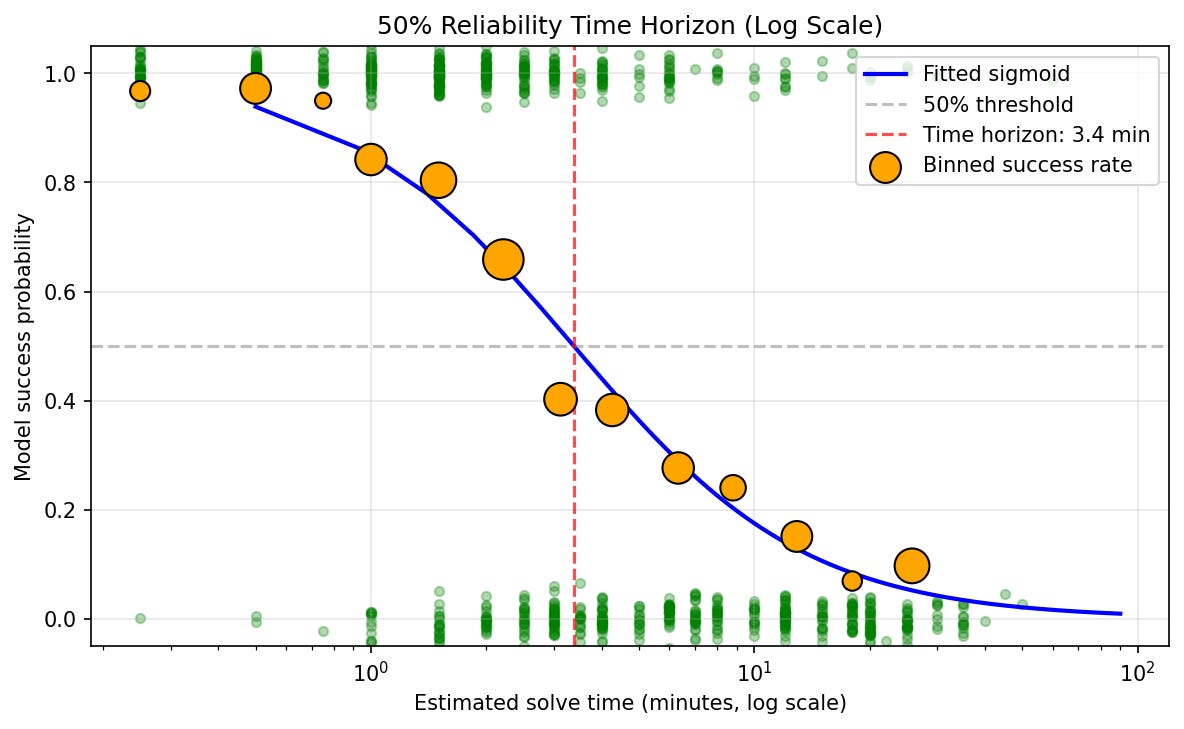

I compute time horizons by asking Opus 4.5 to estimate how long a problem would take for the median AIME qualifier (I give it 4k thinking tokens for this task) and then fitting time horizon using the methodology in Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks. I show and analyze no-CoT math time horizon results in a future post (including historical trends and sanity checks of the methodology). Here I’ll just show log time horizon increase vs baseline performance so we can better understand repeat/filler token performance improvement (and I’ll claim that the methodology is reasonable and passes sanity checks).

(Time horizon results on this dataset aren’t meaningful for GPT-3.5, Haiku 3, and Haiku 3.5, so I’ve cut them from this plot. This is because I don’t have enough problems in the less than 0.5 minute range to get a good fit and Opus 4.5’s time ratings probably aren’t very meaningful below 0.5 minutes.)

My interpretation is that there is some relatively sharp capability threshold at which models become capable of effectively utilizing repeats and then this yields a roughly constant bump in performance of around 0.4 doublings (an increase of ~1.3x). The threshold for benefiting from repeats doesn’t exactly correspond to some absolute no-CoT baseline accuracy threshold but it is correlated with this. Utilization of filler tokens seems to improve more smoothly with capabilities and then caps out at the same uplift.

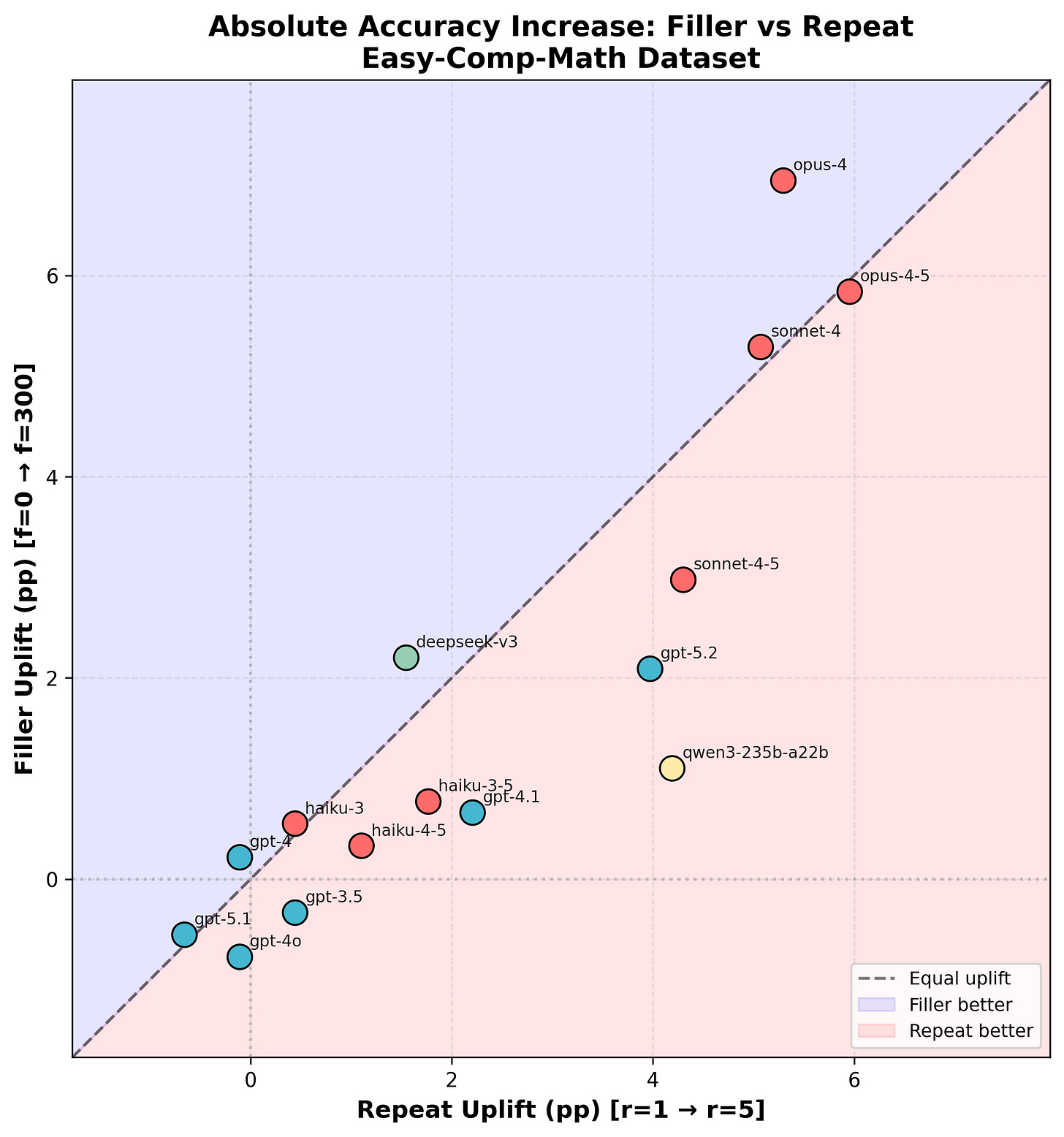

Comparing filler vs repeat

Which boosts performance more, filler tokens or repeating the problem? I find that for a given model the uplift for filler tokens and repeats tend to be similar. The repeat uplift tends to be larger, especially for weaker models. The best performing models I evaluate (Opus 4.5, Opus 4) have basically the same repeat and filler token uplift.

(Note that many of these smaller uplift values aren’t significant and could just be noise.)

Future work

I think it would be most interesting to investigate:

Do filler tokens or repeats help in other domains where models can answer in a single token? Particularly code classification domains like “is this code correct” or “is this code malign/backdoored”. I’m also especially interested in how sophisticated of novel codes models can decode in a single forward pass (with or without a description of the code in context) as a proxy for steganography ability.

What do we see if we apply interpretability tools to the filler tokens or repeats of the problem? Can we use internals to better understand why this helps with the model? More generally it seems interesting to study how models do (surprisingly sophisticated) math problems in a single forward pass.

What does performance (over time) look like on other tasks or distributions where various types of (weak/basic) no-cot meta-cognitive abilities would be helpful?

In a future post, I’ll discuss more general results on no-cot (single forward pass) time horizon for LLMs and how this has changed over time.

Appendix: How helpful were AIs for this project?

Almost all of the literal code for this project was written by Opus 4.5 or Sonnet 4.5. This was a relatively straightforward greenfield project, so I think the AI uplift is particularly large and it’s pretty plausible that Opus 4.5 would be able to autonomously implement some relatively minimal version of this project end-to-end given a description. I think if I was well practiced at using Claude Code to do this sort of project the level of uplift would have been about 3x-5x. In practice, I think I got around 2x uplift, though this might depend on how valuable you think various plots are. (I did more plotting and nicer plotting than I would have done without AIs.)

The uplift is larger if you include PDF parsing to create the dataset.

Appendix: more information about Easy-Comp-Math

To run these experiments, I wanted a dataset of uncontaminated math problems which are pretty easy (e.g. a median AIME participant can solve them in 1-10 minutes) but are as interesting/diverse/tricky as possible subject to this constraint. I found that Hendrycks MATH, past AIME, and past AMC were all strongly contaminated with Opus 4.5 getting 80-90% accuracy with no-CoT and where the solve rate was unrelated to assessed difficulty (as rated by Opus 4.5). Having a solve rate that doesn’t seem related to difficulty is pretty strong evidence for contamination as we’d strongly expect these to be related in the absence of memorization.

I assembled a dataset of 907 mostly easy competition math problems from a variety of sources. This dataset is pretty mediocre and it’s likely that the label accuracy is less than 98% due to poor parsing or other issues.

My data comes from Hungarian high school math competitions (~250 problems), MATHCOUNTS (~600 problems), and the most recent HMMT (~40 problems). For Opus 4.5 and Opus 4, I see a reasonable looking (smooth) relationship between solve rate and estimated difficulty (and estimated completion time) for each of these datasets. I also don’t see large differences between different subsets in solve rate by difficulty. For most of this dataset, the answer isn’t immediately next to the problem statement making pretraining contamination less bad. Other than HMMT (which is after the cutoff), these problems are either from relatively obscure sources or are relatively easy making it less likely that AI companies would RL on this data. My best guess is that most of these problems are in the pretraining corpus but probably not in a context where the answer appears along with the problem. Probably a subset of this data appears in the pretraining corpus with problems and answers in the same document, but if this isn’t repeated too many times, memorization effects might not be fatal and certainly don’t seem to be present.

Here is Opus 4.5’s no-CoT (r=5) solve rate by human solve time:

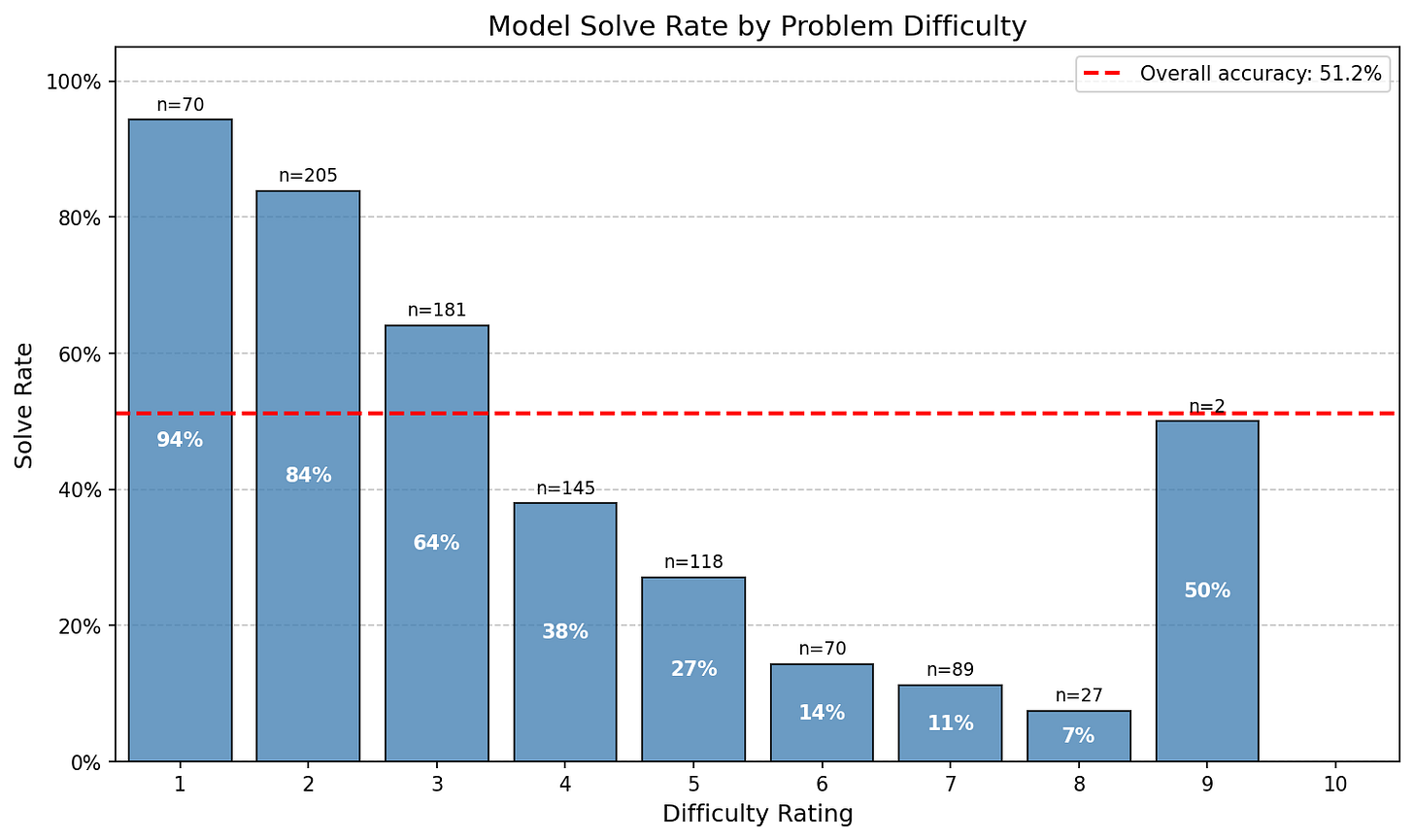

And by estimated difficulty (see below for details):

Here are 10 randomly chosen example problems in the 3-4 minute estimated solve time range (Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets problems in this range right around 50% of the time):

A criminal octopus has eight tentacles. When caught by the police, they want to handcuff its tentacles in pairs using four handcuffs. Each tentacle is handcuffed to exactly one other tentacle. How many different ways can they do this? Two ways of handcuffing are considered different if there is at least one tentacle that is hand- cuffed to a different tentacle. [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

In a triangle ABC, sin(A) = 3/5 and cos(B) = 5/13. The value of cos(C) = p/q, expressed in lowest terms. The answer is pq. [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it wrong]

The points (1, 7), (13, 16) and (5, $k$), where $k$ is an integer, are vertices of a triangle. What is the sum of the values of $k$ for which the area of the triangle is a minimum? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

In a soccer league with 8 teams, each team earns 2 points for a win, 1 point for a tie and 0 points for a loss. The league standings are based on the total points earned by each team. After a total of 40 games, each team has played the same number of games and the top four teams have earned point totals of 15, 13, 12 and 11 points. There is one team in fifth place and three teams are tied for sixth place. How many points has the fifth-place team earned? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it wrong]

For all real numbers $r$ and $s$, define the mathematical operation # such that the following conditions apply: $r \# 0 = r$, $r \# s = s \# r$, and $(r + 1) \# s = (r \# s) + s + 1$. What is the value of $11 \# 5$? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

How many positive 3-digit integers are palindromes and multiples of 11? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it wrong]

An isosceles trapezoid has legs of length 30 cm each, two diagonals of length 40 cm each and the longer base is 50 cm. What is the trapezoid’s area? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

A bag contains red marbles and blue marbles. If two marbles are chosen at random without replacement, the probability that both marbles are red is $\frac{1}{5}$, and the probability that both marbles are blue is also $\frac{1}{5}$. How many marbles are in the bag? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

What is the area of the region bounded by the three lines with equations $2x + y = 8$, $2x - 5y = 20$ and $x + y = 10$? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it wrong]

If $(x^2 + 3x + 6)(x^2 + ax + b) = x^4 + mx^2 + n$ for integers $a$, $b$, $m$ and $n$, what is the product of $m$ and $n$? [Opus 4.5 with 5 repeats gets it right]

(I omitted problems that are more than 1 line long for ease of display.)

For MATHCOUNTS, I use only national/state competitions and only target, team, and sprint (excluding countdown round).

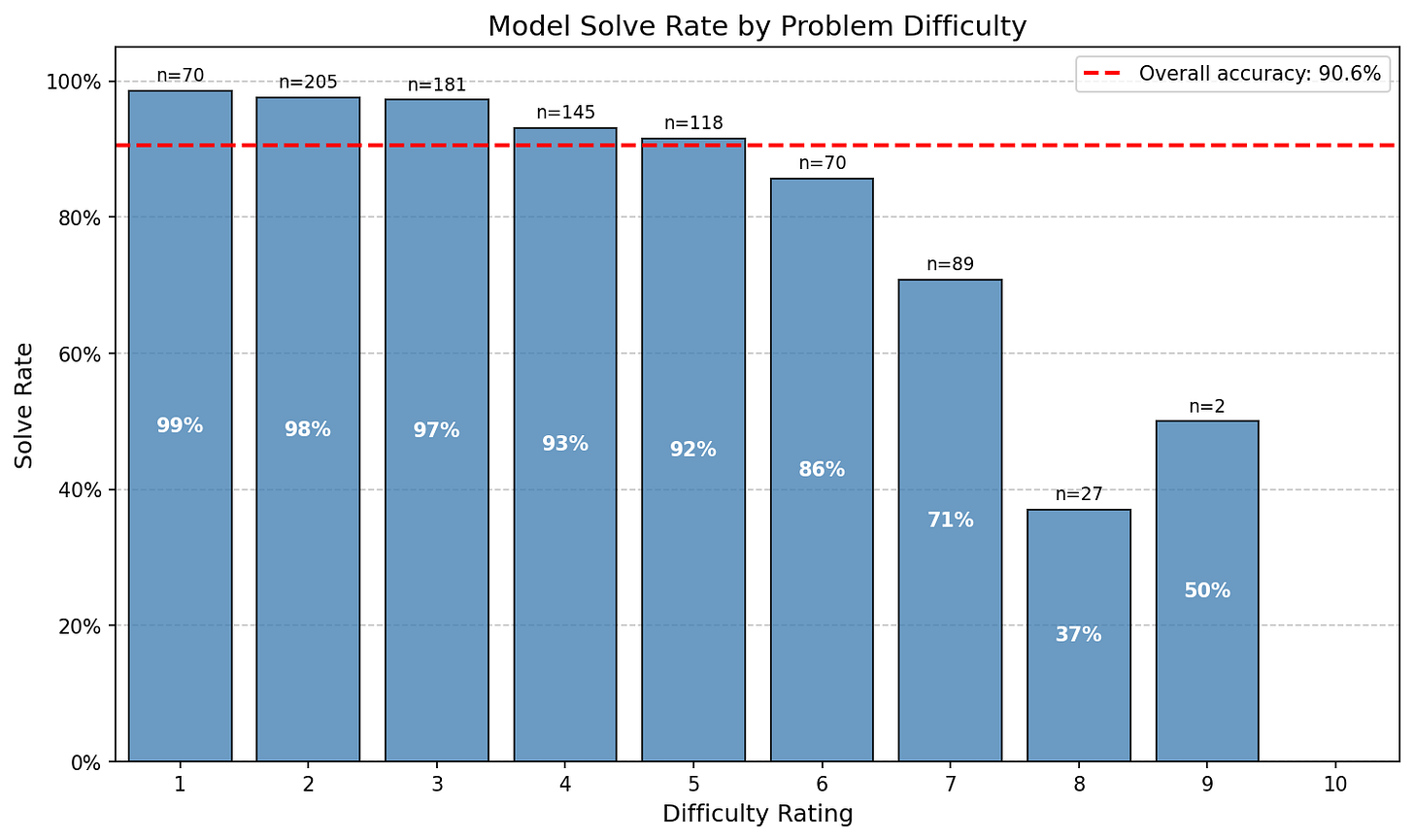

I use Opus 4.5 to parse PDFs with no serious validation or checks.9 However, I do verify that Opus 4.5’s solve rate with reasoning is high. I get that Opus 4.5 solves 90.6% of problems with 12k reasoning tokens and 97.6% of problems rated as difficulty 3 or lower (implying that many of the problems it gets wrong aren’t due to label error unless there is a correlation between label error and difficulty). (See below for description of the difficulty scale I use.)

Here are the solve rates by difficulty with reasoning:

I intentionally don’t make this dataset easily available to reduce the risk of contamination; please contact me for access to the dataset.

I use the following prompt to get Opus 4.5 to estimate difficulty and solve time:

Rate the difficulty of the following math problem and estimate how long it would take to solve.

DIFFICULTY RATING (1-10 scale):

- 1 is an easy grade school math problem (basic arithmetic, simple word problems)

- 3 is a challenging middle school or early high school problem—think algebra, basic geometry, or problems from competitions like AMC 8 or early AMC 10

- 5 is a solid high school competition problem, like a mid-range AMC 10/12 question

- 8 is a typical AIME problem

- 10 is harder than the hardest AIME problem (approaching olympiad level)

SOLVE TIME: Estimate the median time (in minutes) it would take for a typical AIME qualifier to solve this problem. An "AIME qualifier" is a high school student who scored well enough on the AMC 10/12 to qualify for the AIME. Consider that these students are strong but not necessarily top competitors. Use fractional minutes when appropriate (e.g., 0.25, 0.5, 1.5, 2.5) - very easy problems may take less than a minute.

Consider factors like:

- Mathematical concepts required

- Number of steps to solve

- Creativity or insight needed

- Computational complexity

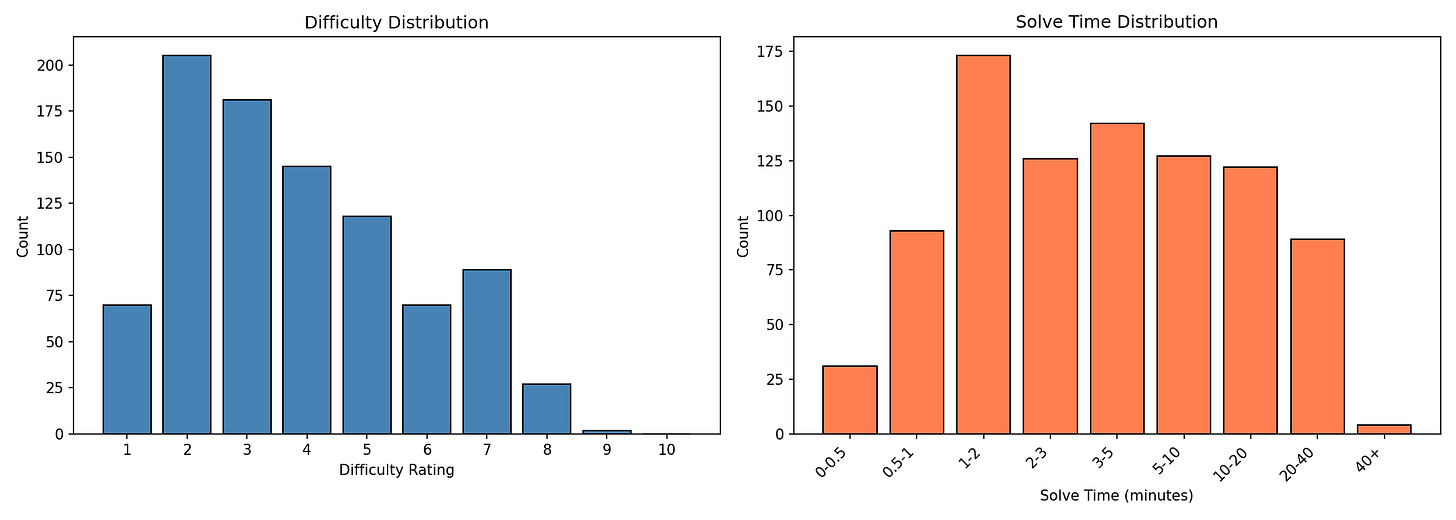

This yields the following difficulty and solve time distribution:

Appendix: tables with exact values

See the corresponding section of the LessWrong cross-post.

Appendix: more plots

See the corresponding section of the LessWrong cross-post.

Appendix: significance matrices

See the corresponding section of the LessWrong cross-post.

As in, they can’t do this without specialized training. Let’s Think Dot By Dot demonstrates that LLMs can be trained to leverage filler tokens within a narrow algorithmic task.

Counting from 1 to 300 like “Filler: 1 2 ... 300”.

This dataset consists of around 600 (easy) middle school competition math problems from MATHCOUNTS and around 300 high school competition math problems from relatively obscure Hungarian high school math competitions. The problems are often very easy and require approximately no insight beyond basic algebra skills.

This demonstrates that while filler tokens can’t fundamentally overcome serial bottlenecks due to a limited number of layers, they can help solve very serial problems. See here for discussion.

I do have some other forthcoming results demonstrating that repeats are helpful for multi-hop latent reasoning (including smoothly increasing in helpfulness with more repeats up through r=20 depending on the exact model). E.g. “The atomic number of (the age Euler was when he died)” is a 2-hop (latent) reasoning problem. But I don’t know if they are helpful for math problems other than via helping with arithmetic; I’d currently guess they are.

I don’t have filler token data on Opus 3, Sonnet 3.5, Sonnet 3.6, and Sonnet 3.7 but I do have repeat token data.

In retrospect, I probably should have used the same r and f for both datasets for simplicity.

For instance, if the model improves from 40% to 50% that would be a 25% improvement.

I did this in a very ad hoc way with some PDFs parsed on claude.ai and some done via the API with particular instructions. In practice, Claude sometimes wrote code to parse the PDFs and sometimes copied out the problems “manually”. Most problems were parsed out of PDFs “manually” and I found this ultimately worked best. For one dataset, I parsed answers in two different ways and then checked for consistency and resolved issues in some reasonable way.

I'm not sure I understand. Are you saying that the model somehow encodes problem relevant information into the filler tokens? I could imagine it using some sort of binary encoding with alternating white space characters. But is there evidence of that or is it just that somehow having filler tokens makes it better for an unknown reason?

very interesting (and a bit concerning?)!

we have tried using DeepSeek v3, and it didn't show statistically significant gain from filler tokens, but we didn't care about contamination on the test dataset.